How Old is Not How Mature: Understanding the Different Rates of Child Development

In every classroom, on every sports field, and in every dance studio, you’ll find children of the same age who are not at the same stage of growth and maturation. Some are racing ahead physically and emotionally, while others are still finding their footing. It’s a common misconception that age equates to maturity and whilst all children follow a similar path they do it in their own time.

The Science of Growing Up

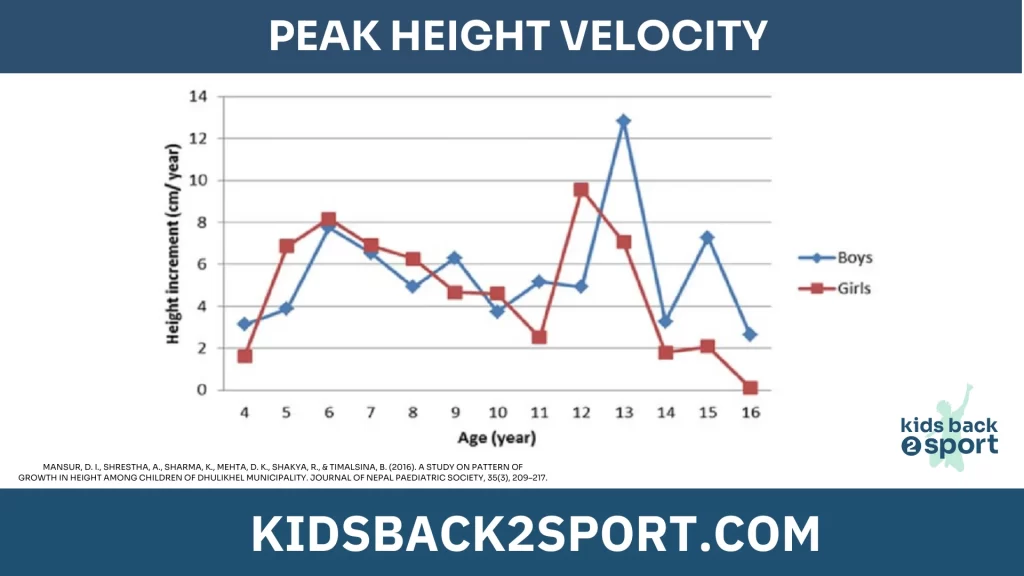

Most children go through a major growth spurt during adolescence, a phase known as Peak Height Velocity (PHV). This typically happens around age 11 for girls and around age 13 for boys – but these ages are only averages. In truth, two children born in the same week could be up to three years older or younger than their peers in terms of biological maturation. Some may be up to 28cm taller or 8kg heavier and this can make a significant difference in some junior sports.

This variation brings challenges for both early and late bloomers. While some breeze through the physical changes, others struggle with growing pains, reduced coordination, or mental stress as they try to adapt.

Early Developers: The First to Grow

Children who hit their growth spurt ahead of peers are often seen as “early developers.” These kids may grow faster, become stronger, and often stand out on sports teams due to their size and power. As a result, they might get selected for elite teams and enjoy access to better coaching.

But early success can come with hidden drawbacks. Relying on size alone may mean they neglect other critical skills, such as technical ability or creativity. These children might never have to experience rejection or failure – which can make them less resilient when those setbacks eventually come.

For parents, it’s easy to get swept up in the success of an early developer. But it’s important to challenge these children and provide experiences where they don’t always win. Developing grit, work ethic, and a well-rounded skill set is crucial – especially as their peers eventually catch up in size and strength. Without that support, the “superstar” label can become a burden rather than a badge.

Late Developers: Quiet Grit and Long-Term Potential

On the other end of the spectrum are the “late developers.” These are the kids who, for now, might be smaller, slower, or seemingly less capable. They often must work harder just to stay competitive, and this can lead to frustration, fatigue, and even self-doubt.

But late developers are often the ones who build the strongest foundations. With fewer physical advantages, they tend to refine their technique, improve their tactical awareness, and develop emotional resilience. Many top athletes – including football stars Harry Kane and Kevin De Bruyne were late developers who faced setbacks as juniors but eventually surpassed their early-developing peers.

The challenge is keeping these children engaged. Repeated setbacks can erode confidence. Highlighting role models and success stories of other late bloomers can help maintain motivation and belief in the long-term journey.

Beyond the Birth Date: Understanding True Maturity

In sport and education, we often talk about the Relative Age Effect (RAE) – the advantage older children in an age group may have due to their earlier birth dates. Children born early in the academic year can be more physically mature, perform better, and get selected more often for competitive opportunities. However, being older doesn’t always mean being more mature. In fact, some children born in the first month of a school year may still be amongst the least biologically mature in their cohort.

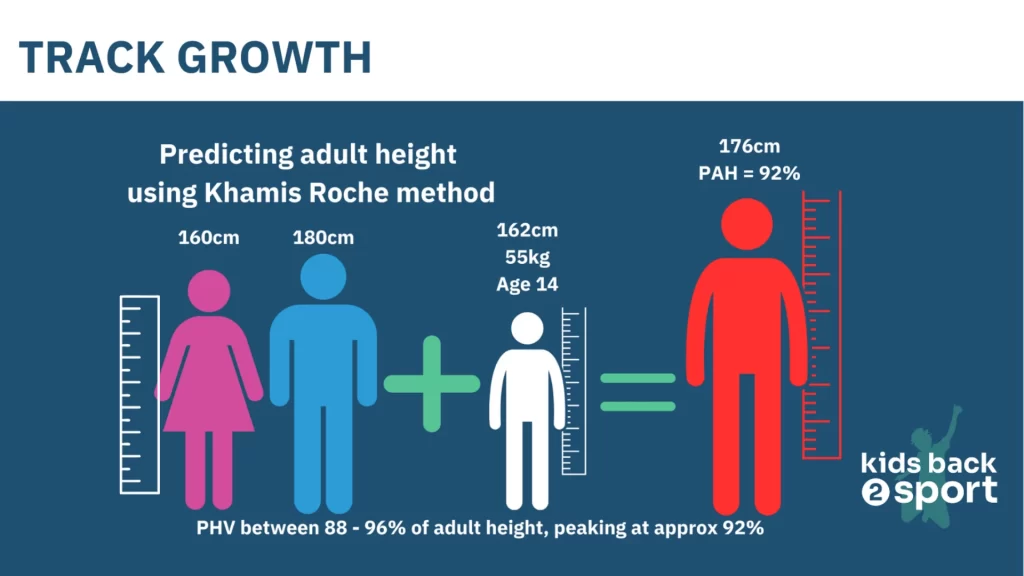

This is where understanding a child’s Predicted Adult Height (PAH) becomes valuable. Tools like the Khamis-Roche method use a child’s current height, weight, and parental heights to estimate how tall they’re likely to grow. When a child hits 92–93% of their predicted adult height, they’re typically in the middle of their adolescent growth spurt.

Tracking these measurements regularly – using consistent techniques – can provide insights into a child’s rate of growth and how close they are to physical maturity. This can help parents understand how children of the same age are not at the same stage of growth and maturation and how better to support their child’s development. Additionally it can help coaches to make more informed selection decisions taking into account not just current performance but likely future success.

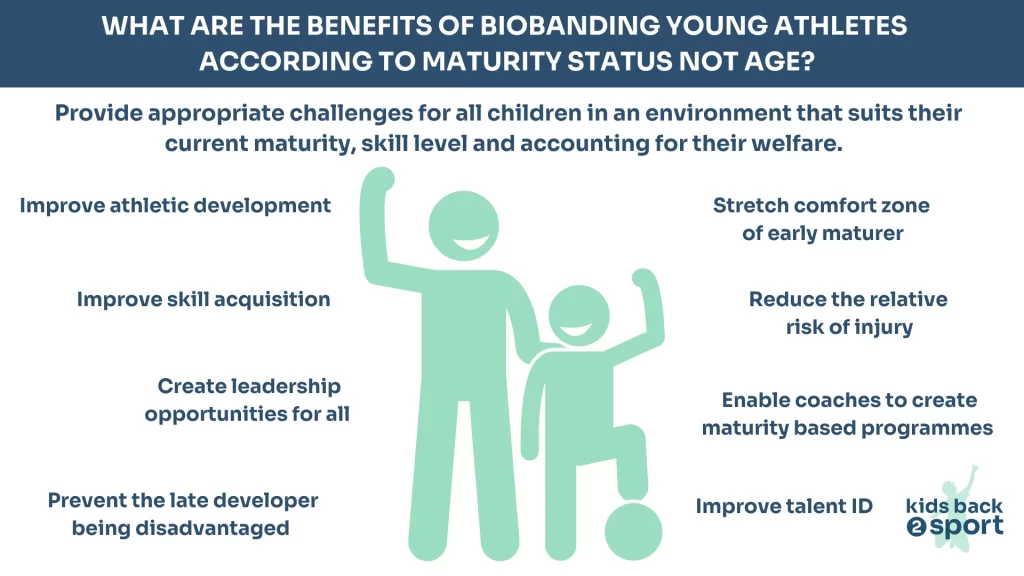

Innovative Solutions: Biobanding and Smart Selection

One innovative approach to navigating different maturation rates is biobanding – grouping children by biological age rather than chronological age for training and competition. In sports like football, this allows late bloomers to lead, dominate, and gain confidence, while early developers are challenged to use skill and strategy rather than just size.

Collecting growth data can also help determine whether a child will reach the necessary height for certain positions – like a goalkeeper in football or a goal shooter or keeper in netball. This type of information is informing coaches to recognise children who may need to develop skills suited to other roles when faced with certain physical limitations needed for the sport.

Managing Growth and Injury Risk

Athletes need to develop strength, movement patterns and sporting adaptations as juniors that make them more robust as they prepare for adult sporting demands. As such, if the child is coping with what they are doing and managing growth spurts without illness or injury, they should be encouraged to fuel well, get adequate sleep and recovery and enjoy their sport. However, some children are more injury-prone during their peak adolescent growth spurt, especially those who:

- Grow faster

- Grow more than 7-8cm in a single year.

- Struggle with coordination during their growth spurt

- Experience niggly injuries and recurrent viruses

- Do not eat enough for the level of activity they do

These children may need to plan for greater recovery days, fuel more and train at sub maximal intensities.

Letting Kids Grow at Their Own Pace

Every child is on a unique developmental path. Understanding that age is not a reliable indicator of maturity – and that early success doesn’t guarantee long-term achievement is vital for parents, coaches, and educators.

Instead of focusing solely on short-term wins, chasing medals or early potential, we should be nurturing resilience, adaptability, and skill. All children will grow when they are ready and developing the skill sets required for long term success is of greater importance than winning cups, medals and titles in those early years.

For more information about growth and maturation please do download the free resource Let’s Talks About Growth and Maturation from Kids Back 2 Sport

Sign up today to the Youth Athlete’s Voice newsletter to read more about athlete development and reducing their risk of injury